Post by Dante on May 8, 2014 15:09:01 GMT -5

667 Reviews:

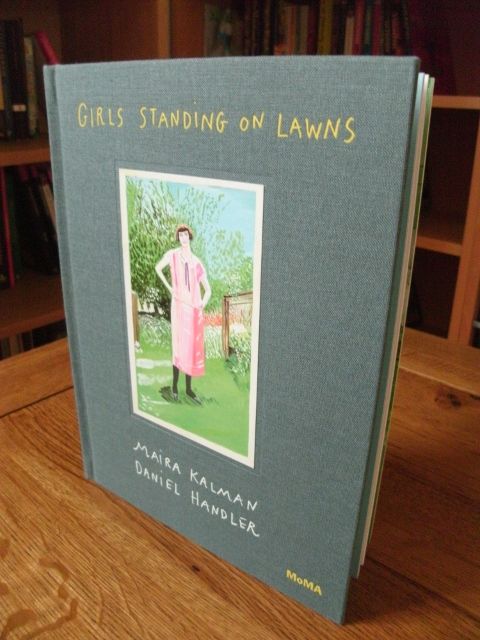

Girls Standing on Lawns

A collaboration between Daniel Handler, Maira Kalman, and the Museum of Modern Art.

If you are a regular follower of Daniel Handler’s work, particularly under the Lemony Snicket mantle, you have probably noticed his fascination with fragmentary, hidden stories evoked by nothing more than a few words or an image, often everyday, usually nostalgic, always unique. It was a great influence on his and Lisa Brown’s recent 29 Myths on the Swinster Pharmacy and, farther back, in the use of vintage archive photography in Lemony Snicket: The Unauthorized Autobiography to relate to and inspire the labyrinthine background of V.F.D. It’s a passion that rises once again to the fore in Girls Standing on Lawns, the first in a series of collaborations between Handler, recurring illustrative partner Maira Kalman, and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which has opened its archive of vintage and vernacular photography for the book – monochrome, faintly sepia-tinged amateur photographs from the early twentieth century. Their subjects? See title. And it’s those which Handler and Kalman have reinterpreted across the pages of this book.

Spread throughout the sixty or so pages of this short book are the original vintage photographs of the era, Kalman’s generously repainted instances of yet more pictures, and Handler’s cryptic, poetic projections of the subjects’ voices, and the narrators’. The photographs are split-second windows into the world of the individuals they capture, with their own personality, dress sense, and surroundings, and the task Handler’s text undertakes is to remind us of their individuality; to speculate about their purpose, their pose, their place in the world, in sparse and philosophical fragments. Why stand on a lawn and be photographed? What does it mean to still be standing there, decades and decades later, when everything has changed but the picture? Why be in a picture, or look at it? Handler breezes over these questions in a style that prompts you to ask those questions yourself; to think about the history of these people in their pictures, and then your own history, what you are doing when you are photographed. In doing so he reminds us to take neither pictures nor their subjects for granted; these are people’s lives, and these are moments in those lives that meant something. It’s these which Kalman is repainting, bringing the faded and colourless worlds of sometimes almost a century ago back to life in vivid and vibrant fashion, washing away the pallor and deep shadows alike with colours that won’t settle for being dull, and an energetically indefinable style that refuses to be fixed in place.

The book itself is also a sort of snapshot of its subject – forty-odd photographs, mostly of girls standing on lawns, with a few variations, but nonetheless united by their common theme. Like a gallery, it asks you to take the time to immerse yourself in these subjects and their questions – and then it’s done, but the pictures are never gone. They’ll still be there next time you visit, so don’t forget them, nor what they stand for.